Sermon preached on the eve of Holocaust Memorial Day based on Psalm 27:1-8, Matthew 4:12-23 and 1 Corinthians 1:10-18 and using resources provided by CCJ (Council of Christians and Jews) for their 2020 theme of ‘Standing Together’.

May I speak and may you hear through the Grace of our Lord; Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Amen.

Tomorrow, the 27th January is Holocaust Memorial Day and its theme this year is ‘Standing Together’ in remembrance of victims of the Holocaust, and the liberation of prisoners from Auschwitz some 75 years ago. We are called quite simply to stand alongside the Jewish Community and with those of all faiths and none, in commemorating the Holocaust, which implies action, commitment, and solidarity. Challenging concepts in a world where an agreement about unity is hard to discover in so many ways.

But try we must… I wonder, if like me, you like to read the words of the Psalm as the choir are singing them? The psalms themselves were written as songs, but they contain a great deal of poignant and resounding poetry with many situations in life. Take verse six for example:

Now my head is lifted up

above my enemies all around me,

and I will offer in his tent

sacrifices with shouts of joy;

I will sing and make melody to the Lord

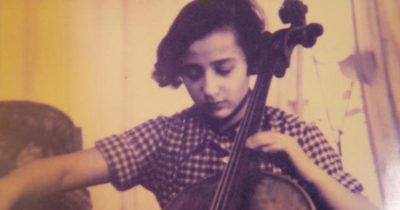

Urban legend has it that the great Jewish violinist, Itzhak Perlman, was once performing to a packed theatre on Broadway, when one of his strings unexpectedly snapped with an audible twang. The audience held its breath, expecting the end of the performance or, at the very least, a break whilst a new instrument would be found. But, Perlman didn’t bat an eyelid. He proceeded to do the impossible – to play the rest of the concerto almost flawlessly on three strings. In explaining the extraordinary feat after the performance, he is said to have remarked: ‘sometimes in life, you have to make music with what is left.’

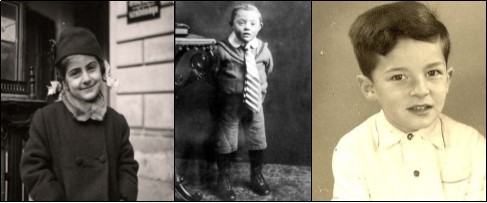

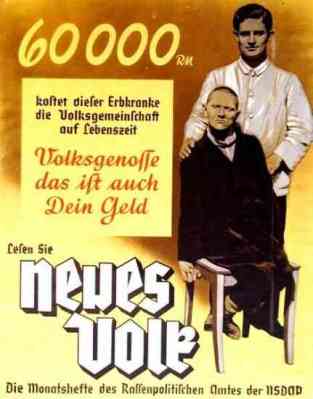

Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis, picked up this idea of making music with what is left in an address to the CCJ – the Council of Christians and Jews, when he pointed out that “None among us can begin to imagine how survivors must have felt as the Nazi regime eventually crumbled and they finally found their freedom. The sense of hopelessness and betrayal must have been overwhelming. There was not (and could never be) any rule book or prescribed structure for how people should rebuild their lives, having had every element of their humanity savaged.

If one Holocaust survivor had somehow summoned the strength to overcome his or her ordeal and live a happy life, it would have been extraordinary. That so many survivors made it their mission to use their experiences to positively impact the world around them, is nothing short of a miracle. You have to make music with what is left”.

The fact that there was a remnant left was also down to the inspirational courage of other individuals, who, despite being faced with multiple political, social, cultural and physical deterrents, found ways in which to offer a lifeline to some of those caught up in the Holocaust. Pushing their differences aside and standing together against tyranny and evil.

In what is also a week of Prayer for Christian Unity, our readings this morning, although not directly, but unsurprisingly, speak to just these issues. In our gospel reading this morning Jesus has returned from the wilderness, with news that John has been taken prisoner, and realising that before he has even uttered a word of the message he was to preach and teach that his persecution had begun, enough that he felt it expedient to leave his home town and go further north, away from the authorities in Jerusalem to live in the north Galilean town of Capernaum.

Matthew also manages to tell us that this will fulfil Isaiah’s prophecy about the ancient land of the tribes of Zebulun and Naphtali, both named after sons of Jacob, the Patriarch and founding namesake of Israel, and their mention is particularly poignant because at the time that the gospel was written, these two tribes had been lost to history for more than 750 years. Originally annexed to the Assyrian empire they had been subjugated by Babylon, Persia, the Seleucid empire and finally Rome, but the people of Naphtali and Zebulun were not forgotten.

Likewise, today, by standing together in Jesus’ name, we must be committed to remember other people beloved to God who were lost to history, but who are not forgotten. Remembering 750 years on, not just these 75… action, commitment and solidarity

The urgency of the need to stand together, is also expressed in Jesus’ calling of the first disciples. A matter so important that there was no time to for internal decision-making or hesitation in their response, the point was to rise and follow at once. We too, must turn from indifference and apathy and rise, follow and act, because if we wait for other’s braver than ourselves to speak out then we permit grave injustices to occur.

The image of the first disciples leaving their nets is still appropriate. Imagine if Jesus were looking to put together a group of people today whom he knew would eventually take over his work and deliver his message for people to turn back to God. You can bet that on top of twelve men there would be at least as many women and children, people with disabilities, homosexuals, trans people, Muslims, Jews and those of other faiths. Just as Jesus called his first followers, so today Jesus calls ordinary people – you and me – in faith, to set aside our tasks and rise to ‘stand together’ in action, commitment and solidarity.

Because faith begins when a group of people come together when they all believe something about a divine being. Last week in Church Alive we tried to come up with five statements that could hold true for all of us whoever we are. Apart from the fact that we were all alive and breathing, there were three other statements that felt right, the first that, ‘God is love’, the second that ‘God loves us’ and the third that ‘we are all children of God’. Whatever faith or none you might confess, we believed these to be true, something everyone could agree on.

Even so, our reading from Corinthians, paints a different picture of what was happening in the early church, where divisions were already appearing, so much so that Paul was appealing to them in Jesus’ name that they ‘should be in agreement and that there should be no divisions among you, but that you should be united in the same mind and the same purpose’.

I personally struggle when Christians exclude people because of their gender or sexual identity. I struggle when they espouse theologies that broke no argument and lead to exclusion of those they disagree with. I struggle when people regard people of other faiths as being represented by a small section who advocate violence and hatred. I struggle with these things. Maybe you disagree with me, but I personally don’t think this is what is means to be a Christian.

Disunity among the leaders and nations of the world, stifles a crying need for the kind of outrage demanded against acts of genocide and other injustices, and disunity within the people of God produces dismay among the hopeful, and allows poverty and human distress to take the place of the joy of restoration. Holocaust Memorial Day is a special opportunity to quietly reflect on the dispossession of God’s human family so totally, and there is a challenge to pray that the present dangers we all see in our personal, social and political life may be prevented, so that the evils that have been experienced within our time will not be repeated.

Following Jesus, rightly remembering the Holocaust, overcoming Christian anti-Judaism: these are not one-off actions. The work to which Jesus calls the Church is a long road that demands daily tasks of healing, justice, and hope. In Matthew’s gospel, that work is carried out under the wider promise of God’s ongoing commitment. As Jesus’ disciples did, there will be times when we falter and stumble. But, standing together, we are strong enough for this journey, for action, commitment and solidarity

Returning to the words of the Chief Rabbi, “We live in challenging times. Hate speech and hate crime are on the rise. Respect for difference appears to be declining. Our society is becoming increasingly polarised. So, what should our reaction be? To fight fire with fire? To match the hateful rhetoric with invective of our own? I believe that we should look to the heroes of the Holocaust: both the survivors and the righteous saviours. We should not be intimidated or cowed. If they were able to make music with what was left, surely we can as well.”

The music of Holocaust victims deserves to be heard loudly and clearly and we need to pick up the strain and add our own voices because if we don’t the words of Pastor Martin Niemoller’s poem will echo in the silence:

First they came

First they came for the Communists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Communist

Then they came for the Socialists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Socialist

Then they came for the trade unionists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a trade unionist

Then they came for the Jews

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Jew

Then they came for me

And there was no one left

To speak out for me

The Holocaust is now 75 years – a lifetime away, and the time when there will be no more survivors left to share their experiences draws ever closer. So today and every day, let us resolve to remember the past, commit to the present and dare to look to the future with hope as we stand together. Amen